The gallery of Roman portraits in the Vasari Corridor

In the systematic reorganisation of the Uffizi Gallery, carried out between 1780 and 1782, Abbot Luigi Lanzi played a leading role. This pioneer of modern archaeology was also responsible for the rearrangement of the series of Roman portraits in the three corridors of the Uffizi, which, thanks to the work of the Abbot from the Marche region, increased both in the number of works and in the quality of the pieces. Choosing the best that the antique market and the grand ducal collections could offer, scattered among the numerous villas and offices of official representation, Lanzi added over forty marbles to the seventy already present in the Gallery, giving rise to a collection of Roman portraits that had few equals in Italy and Europe. Since 1996, the refurbishment of the Gallery' corridors has restored the furnishings of the ancient sculptures in the three corridors to their appearance as documented in the “Atlante di Galleria”, coordinated by Abbot De Greyss in the mid-eighteenth century. This museological choice meant that the portraits chosen by Lanzi, added at a later time than that documented by the drawings of the “Atlante”, were removed from the exhibition spaces to be placed in the storage rooms.

Thus, the exquisite portraits scrutinised with great attention by the Marches-born Abbot were not excluded from tour itineraries because they were deemed expendable, duplicate, or due to aesthetic considerations or fragile conservation status. Rather, in an almost paradoxical twist, the Uffizi deposits became home to significantly important marbles - carefully selected masterpieces from Villa Medici in Rome, the grand ducal palaces, and the premier private collections in Florence. Only the curatorial choices made in the nineties of the twentieth century put an end to the collection conceived by Lanzi, whose richness and importance are well understood from the choice of these forty-seven works now arranged in the section of the Vasari Corridor that runs over Ponte Vecchio, where, after decades of neglect, they have finally returned to the full enjoyment of the public.

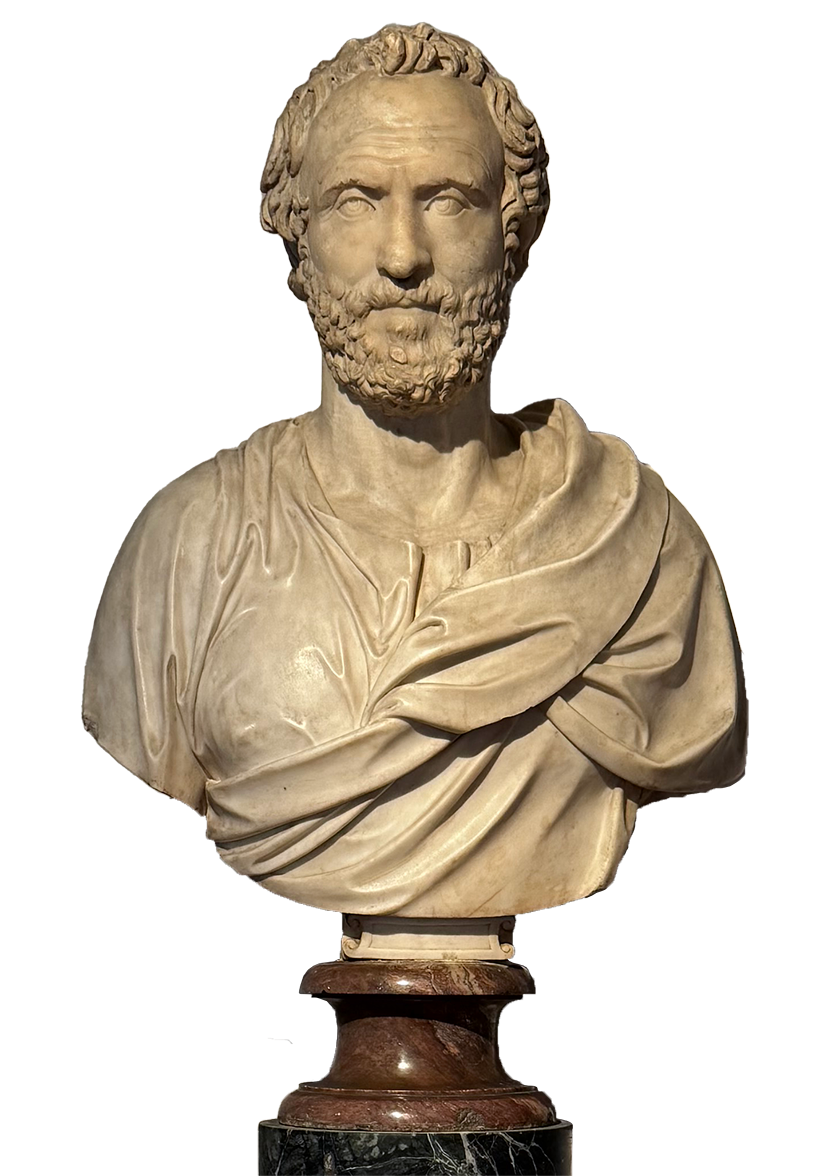

In fact, these marbles offer an effective and extremely high-quality synthesis of the evolution of Roman portraiture from the late Republic to the Tetrarchic age (end of the first century B.C). – End of the 3rd century A.D.). From examples that still bear the influence of the Italic tradition of exaggerated realism, such as the bust of an elderly man 'velato capite', to portraits swayed by Hellenistic pathos, like the magnificent colossal likeness of Cicero, we arrive at the composed classicism of the Augustan age, perfectly illustrated by a dynamic replica of the Augustus of Prima Porta. The full imperial period is evidenced both by official portraits of exquisite workmanship and by private effigies in which we find echoes of imperial models. As such, the fashion for beards among the Antonine and Severian emperors is directly reflected in heads like that of the so-called 'barbarian', while the preference for more compact and geometric forms is evident in works such as the so-called Maximus or the so-called Diadumenian, both dating back to the early decades of the third century A.D.

However, it is above all the female portraits of the first and second centuries A.D. that offer some of the best evidence of the stylistic trends of those years. In particular, what stands out is an exceptional bust of a young woman carved around 15 B.C., in the early Augustan age. Beyond the exceptional strength of the portrait and its subtle psychological introspection, the work stands out because the woman is depicted wearing the stole, the heavy garment worn over the tunic, hiding any type of transparency and shape. This choice, inspired by modesty and temperance, was intended to be a tangible demonstration of the fact that the character portrayed was a supporter of the moralising policy of Augustus who, with the laws enacted between 18 and 16 B.C., tried to put a stop to the spread of moral corruption. In the series of female portraits, moreover, what stands out is a woman with a solemn appearance and a unique hairstyle. It is a vestal, characterized by the infula, the sacred bandage that surrounds her head. Finally, one cannot help but remember the clear portrait of Sabina, wife of Hadrian (117-138 A.D.), or, again, the refined faces of the Antonine age, true masterpieces of psychological introspection. These works, depicting wealthy ladies who lived in the central decades of the second century A.D., can be dated with a good degree of certainty thanks to the complex hairstyles, which replicate those adopted by the empresses of the period and are evidenced by the coniage.

With the portrait gallery now reconstituted in the Vasari Corridor, the museum regains an important piece of its historical collections. Only now can we fully grasp the meaning behind Luigi Lanzi's words. Discussing the portrait series in the gallery, which he curated, he expressed understandable pride by declaring that “a series up to Gallienus has been assembled, which could almost be described as complete”.